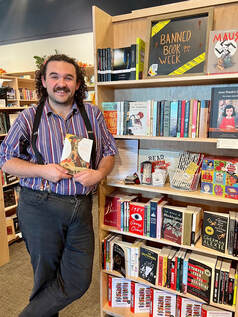

“Embrace diversity. Unite-- Or be divided, robbed, ruled, killed By those who see you as prey. Embrace diversity Or be destroyed.” - Octavia Butler, Parable of the Sower) Books for me have always been a bridge to something else. A bridge to a fantastical realm that I wish existed. A bridge to a happier outlook when I am feeling down. A bridge to a life that I don’t have the perspective to understand. A bridge connecting me to the author and every person touched by the words they put to paper. During the pandemic I started a reading group with some friends online in a desperate need for community when I, like many others, was feeling so alone, grappling with the world around me. We read a few books but the one that stopped me in my tracks and built a bridge for me was Parable of Sower by Octavia Butler. If you have not read the book, it is the story of Lauren Oya Olamina, told through her journal entries as she is forced out of her tight knit religious community and into a climate ravaged version of California. She along the way builds a family, creates a doctrine that we could all do good living by, and grows something new out of the crumbling world around her. That’s not even the bare bones of what the book actually becomes for the reader, but it’s the easiest way I can describe it at this moment. Parable of the Sower, like many great banned books, takes on big discussions of poverty, religion, race, womanhood, etc. The reasonings offered up for banning the title are often that the discussions of the aforementioned topics are too tough for children or young adults to be confronted by. “These things frighten people. It’s best not to talk about them.” "But, Dad, that’s like … like ignoring a fire in the living room because we’re all in the kitchen, and, besides, house fires are too scary to talk about” (Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower). Reading books from a young age has always been an exercise for me in expanding my horizons and building bridges to the world around me that my privilege or perspective did not allow me to see otherwise. This book helped me to grapple with so many of the tough conversations happening in the midst of the global pandemic. From kids to adults, books like this help us to think about, discuss, and come to terms with the hard realities happening around us. Books like this build bridges so that we can see each other and empathize across the gender spectrum. Books like this help those in the middle and upper classes build bridges to understand the lived experiences of those in poverty. And books like this build bridges so we can become not only a more equal society, but also a more equitable, and most importantly more compassionate society. Banned Book Week works to bring to the forefront that we are not banning merely words printed on pages. We are banning diversity of perspective. We are silencing voices that don’t align with the imagined realities some in power have decided is canon. Banned Books Week serves to remind us that we must fight these challenges to these lived realities and keep reading free. “Freedom is dangerous but it's precious, too. You can't just throw it away or let it slip away. You can't sell it for bread and pottage.” (Octavia E. Butler, Parable of the Sower)

2 Comments

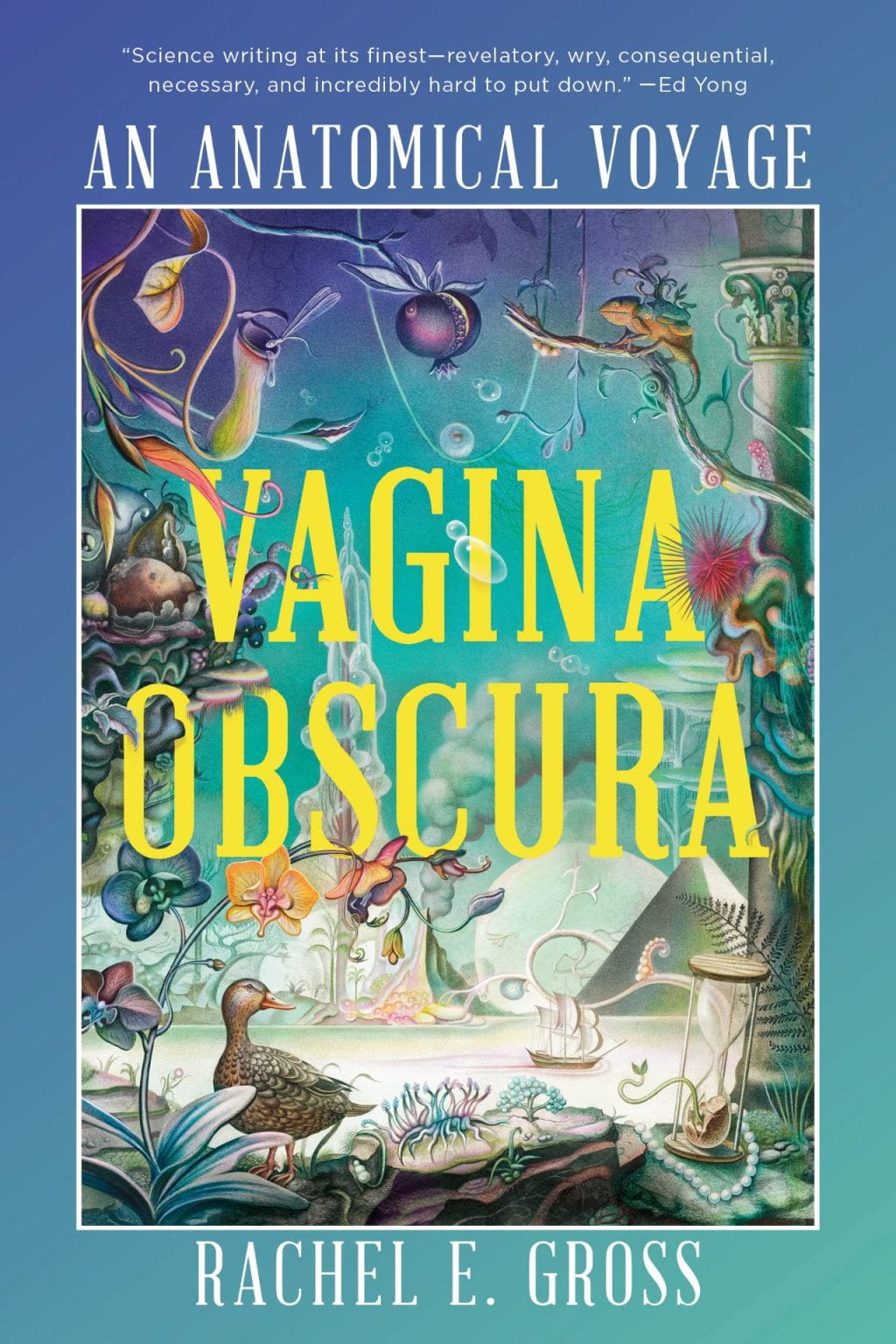

What was the biggest challenge or surprise you encountered when writing this book? I set out wanting to take readers on a wonder-filled journey to the center of the female body — a Magic School Bus ride that would enthrall and empower people about their own biology. But I quickly learned that our knowledge about the female body was filled with holes, myths, and misconceptions. So instead, I had to write, in a way, a book about why we don’t know what we don’t know. That turned out to be a much more difficult challenge, but also much more rewarding. I have seen only rave reviews (no doubt well-deserved!); I wonder if you have faced any pushback or criticism from any groups or regions, given the rise of banned books, the cultural divide in this country…and how you can respond to a parent or group uncomfortable with this subject? There is always criticism! Initially, I got a few critical reviews out of the UK pushing back my decision to dedicate the last chapter of the book to the history of gender affirmation surgery. To me, this chapter is central to what the book is about: it reveals better than any other how medicine’s assumptions about gender and enforced ideals about the female body harm anyone who falls outside that standard, including intersex people, nonbinary people, and trans men and women. It shows how medicine has often historically been a force for gatekeeping womanhood, in ways that have harmed all of us. A few comments also accused me of bringing feminist bias to the topic, particularly in the sections where I point out the deep similarities between all bodies and challenge the idea that male and female are opposite sides of a spectrum. I found that a bit ironic, because the book points out how so much scientific knowledge that has been considered objective and neutral has, in fact, been tinged with masculine and racial bias. I’m a science journalist, and my conclusions come from emerging science showing that similar processes of regeneration happen in male and female bodies; that our reproductive systems stem from the exact same structures in the womb; and that we all rely on the same hormones to power our brains and bodies.

Medicine has a particularly entrenched culture; in some ways, the process of going through medical school means absorbing the values of that culture and learning to look at patients and their bodies in one way. Because of that, you can be a woman and still ultimately become a doctor or researcher with the same, let’s just say masculinist, view. So I think it’s going to take researchers who are willing to challenge the actual paradigm of medicine, its paternalistic history, its historic devaluing of female pain, and the way it often decenters patients as experts on their own bodies. And that needs to be a concerted movement of patient advocates, doctors, and the public, not just a few individuals.

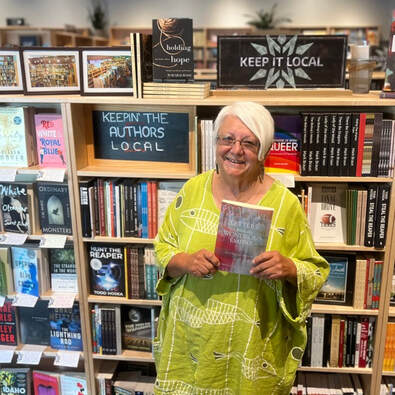

In places you invite your reader into the narrative, to imagine their body, their legs, and their vaginas. Can you talk about choosing to invoke your readers as people with vaginas? In the past, when I read books and articles about this topic, I often had the sense that I was not the intended audience. Even if I was reading a women’s magazine, the “sex tips” and sexuality articles were always about some assumed, heterosexual male partner and his pleasure. My goal was to write the book I wished I had when I was younger and beginning to explore my body and my sexuality. And that meant writing for those who actually have this anatomy, and deal with the lived experience of having society often treat their bodies as shameful, broken, or as “medical mysteries.” It also meant invoking a sense of wonder and curiosity about the female body, which I felt was lacking. My intention was never to alienate readers who don’t have this anatomy, but to provide an alternative — I would say necessary — view of the female body as something resilient, dynamic, and powerful. Were you surprised by how much the book seemed to strike a chord with readers? I began writing this book at a time when reproductive rights were under siege and “fetal heartbeat” laws were sweeping the nation; I finished it shortly before the Dobbs decision. I think given this context, it was pretty clear why a book about the ways medicine has misunderstood and underestimated the female body was important. I looked to history to show how medicine viewed the female body as primarily a reproductive vessel, ignoring the ways in which these organs are also critical to our sexuality, immune system, and overall health. As it turns out, these are some of the same truths that are being overlooked today. So the book turned out to be unexpectedly timely, or untimely, depending on how you look at it. Any future books in the works? I’m honestly not quite ready to embark on the next book! But I am continuing to look at hidden biases within medicine, a theme that emerged from this book. I recently started a column for the New York Times‘ science section called “Body Language,” which looks at the origins and consequences of some of the more striking medical language doctors use, from “incompetent cervix” to diseases named after Nazi doctors. I’m really interested in the doctor-patient relationship and how it’s changing, and language is one way into that important question. What do you like to read for pleasure? I love fiction, and feel I learn so much about narrative structure and the art of evoking character by reading it. Most recently I read Holding Pattern, a punchy little novel about a second generation Chinese immigrant who pursues a PhD in the haptics of touch, but ends up becoming a professional cuddler. I also love sci fi and speculative fiction; I just blew through Mother Night, a World War II book about an American spy who “plays” a Nazi propagandist and finds the lines between his two identities blurring, by Hoosier Kurt Vonnegut.  Cynthia Mosca is author of Letters from a Wondrous Empire: An Epistolary Memoir, chronicling her time teaching school in Ethiopia with the Peace Corps from 1967-69, based on letters she wrote to her family back home. This (then) single woman in her 20s from Wisconsin fell in love with Ethiopia, and remains so today! Save the date: We're hosting a talk with Cynthia on Tue, Sep 26th. (Mitch) What compelled you to write this book? (Cynthia) COVID. You know, I had started cleaning things out and ran across all these letters I had written from Ethiopia that my mother and my aunt had saved. I thought, "Maybe I should read these, it’ll be a trip down memory lane." And it was. Except there were parts I had no recollection of. So I got in touch with other people from Ethiopia I'd lost touch with over the years. I was in a writing group. And it just became this project. Which writing group were you in? I was in a writing group at the Unitarian Church with John Woodcock. I told them I would read these letters and respond to them. They encouraged me. So I started doing it, and it became more and more involved. How did you find a publisher? There's a group called the Peace Corps writers imprint. I submitted the book to them, and they accepted it! How did you connect to Morgenstern's? Not long after Morgenstern's opened, The Herald Times did a really big article about me and the book. I was out of town, but my partner Dennis dropped off a copy of the article and the book at the bookstore. I don't think you were doing events in-store at first. It took a while, but here we are! Let's rewind a bit: What did you do after the Peace Corps? I moved to Chicago, got married, and raised my kids there. I continued teaching. I taught various subjects including art and English as a second language, also became the director of a bilingual program in a K-8 school district. What brought you to Bloomington? When My partner Dennis and I retired, he decided he couldn't handle the traffic in Chicago anymore. So we looked around. We had a friend who lived in Bloomington who thought we'd really like it. So we drove into Bloomington. We drove past Baker's Junction, and then the Tibetan Cultural Center. and I was like, "Oh, my God, I love this place, I'll fit right in." And you are still very involved with Ethiopia? Yes! I'm President of the Ethiopia & Eritrea Returned Peace Corps Volunteers. I'll be donating royalties from the book to Save the Children, The International Rescue Committee, and Doctors Without Borders through Peace Corps volunteers in Ethiopia and Eritrea. We're also starting a new relief project through Save the Children for nine schools and two health clinics that were really affected by the civil conflict. I also support another organization called Selamta, which provides family homes for Ethiopian orphans. That's amazing. I wouldn't be able to keep up with you (laughs). And I look forward to speaking with you more on September 26th! |

Archives

January 2024

CateGORIES |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed